Dr Keith Burgess (Sleep Physician) has been prescribing Mandibular Advancement Devices (MAD’s) for 25 years and has taken the time to answer some of the common questions asked by patients considering the use of a MAD for the treatment of their Obstructive Sleep Apnoea and/or snoring.

1. What severity of obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is suited to having a two piece adjustable mandibular advancement device (MAD)?

The best suited are those patients with “simple snoring” or mild to moderate severity OSA.

2. What other factors do you consider in recommending MAD? (E.g: weight, tongue size snoring etc…)

There are data that suggest that obese patients do not do as well as the non obese.

But, that is less of an issue than which treatment will the patient accept and use?

There is no point pushing CPAP therapy if the patient will not accept it. Adequate dentition is essential. The patient must have at least 8 strong teeth top and bottom to use a MAD, and the more the better.

3. What is the process for having a MAD fitted?

Referral to an experienced dentist.

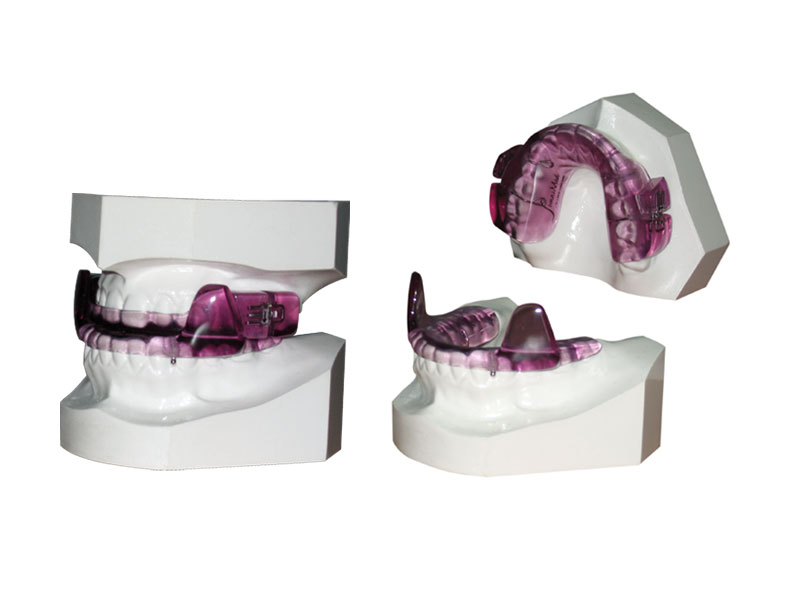

The dentist takes an impression or a computer scan of the patient’s teeth.

The mouldings or computer file are then sent to a lab who manufactures the device.

The patient returns to the dentist, usually three weeks after the assessment, to have a test fit of the MAD. Any discomfort issues are dealt with, and often the device is advanced a little.

The patient then uses it for two weeks without adjustment.

They then return to the dentist for review and another advancement.

The dentist then shows the patient how to advance it and sets up a schedule, or books appointments for further advancements.

Once the snoring stops, or is much reduced, or the patient reaches 2mm in front of “edge to edge” the advancing stops.

The patient is then reviewed by the sleep physician and a follow up sleep study arranged.

4. Is it important to be re-tested once the device is fully adjusted?

Yes. Except for those patients who only had snoring without OSA, who do not need another study. For all those with OSA they should be restudied to make sure that the OSA is being controlled at that degree of advancement. Often a further adjustment is required.

5. What is the rough cost of a device?

The cost depends on the dentist. To my knowledge the fee ranges between $1500 and $3000 which includes the device itself and the dentists' time and expertise.*

*Note these costs are estimations and you will need to discuss your expected costs with your dentist

6. How long do they last?

If the patient does not tread on them nor their dog eat them (common problems apparently) they should last 5 years.

7. Are there any side effects and/or contraindications to MAD treatment?

There are few contraindications: a strong gag reflex and inadequate dentition are the main ones. Temporo-mandibular joint problems are NOT a contra indication.

Most patients will have some degree of bite change due to the device. Most patients do not mind and very few have to stop using it because of marked bite change. Unfortunately, it is not possible to predict who will suffer from this and who will not. In my experience it does not appear to be related to the degree of advancement.

Dr Burgess has no financial interest in any company that manufactures MAD’s. He is the sole Medical Director of Peninsula Sleep Clinic.